Published: 10/02/18, Last updated: 6/06/23

Introduction

(last updated 11/2/2020).

Americans eat a lot of chicken — about double the amount of beef or pork we eat. Chicken has gotten so popular in part because it’s become so inexpensive to buy. And as chicken has gotten cheap, it has become bad for nearly everyone involved in producing it, including farmers driven into bankruptcy, poultry plant workers suffering from terrible injuries, birds bred to grow so fast they can’t stand up and an environment polluted by excess manure. The companies at the top making all the profits are doing well — but that’s about it. Even for consumers, chicken is bad: it may be cheap, but industrially produced chicken is often bland and flavorless and can be contaminated with salmonella or other dangerous bacteria. No matter how you slice it, the foodprint of industrial chicken is not sustainable and needs to change.

Chicken production developed as it did, in part, because the animals, being small in size and fast to grow, fit easily into a mechanized system whereby they are turned into cogs in the wheels of industry. But a different system is possible; a different product is possible. Chicken meat can be a nutritious and flavorful source of protein, and the animals can be a beneficial part of a pasture-based diversified farm system, eating bugs and increasing soil fertility with their manure. Farmers can get a fair price for the birds they raise, and workers in processing plants can be paid decently and treated humanely. There are so many diverse aspects to the current system that there is not one single, overall solution, but many ways in which the industry could be improved.

What Poultry Should Be

Chickens should be raised with maximum consideration for the health and well-being of the farmers, workers, animals and the environment.

This means that chickens are:

- Slow-growing enough so that they can move around easily on legs that can support their body weight.

- Not given antibiotics and other drugs prophylactically.

- Spared unnecessary suffering and treated humanely throughout their lives.

- Not housed at a density whereby their waste is too much for the local environment to absorb.

- Raised by farmers who can make a decent return on investment, are allowed autonomy in their farm decisions and who are not living at the edge of bankruptcy.

- Processed by workers who are paid a living wage and treated fairly.

Poultry should also be:

- Packaged with meaningful and verifiable labels that consumers can understand.

- Nutritious and delicious.

Background

In 1960, per capita consumption of chicken was not even one-third that of beef or pork; now it’s practically double.

Chickens raised for meat are called broilers, or meat birds, as opposed to hens raised to lay eggs, which are called layers.

Broiler Chicken Lifecycle

Conventional broiler chickens begin their lineage at the breeder farm. Hens and roosters are kept together, and the hens lay fertilized eggs. The eggs are removed and incubated in machines for about three weeks; when they hatch, the chicks are normally vaccinated against multiple common diseases and shipped to the grower within a day. They spend six to seven weeks in a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO), a large barn with feed, lighting and temperature designed to make them gain weight as quickly as possible. When the birds reach the designated weight, a team of workers (called “catchers”) clears the barn and transports the chickens to the processing plant, where they will be slaughtered and processed into cutlets and nuggets.

- CAFO

- Stands for concentrated animal feeding operation — a large barn with feed, lighting and temperature designed to make animals gain weight as quickly as possible.

The Chicken Industry

The conventional poultry industry has changed dramatically over the last 70 years. Many people used to keep a few chickens on a farmstead, primarily for eggs. Eggs were traditionally allowed to hatch only to produce the next generation of laying hens. The male chicks, being useless for egg production, were often reared for meat, but doing so was relatively expensive. So, for much of U.S. history, chicken was reserved for special occasions, such as Sunday night family dinners.

Production of broiler chickens nearly tripled between 1940 and 1945, in part because poultry, unlike other meats, was not rationed during World War II.1 Additionally, in 1942, the U.S. government put the entire production of the Delmarva peninsula (a large land mass that includes parts of Delaware, Maryland and Virginia) under contract for federal food programs, providing a huge boost for the area, which remains one of the primary broiler production areas in the country.2 Two “Chicken of Tomorrow” contests in 1946 and 1951 were the beginning of breeding some chickens specifically for meat, rather than only using males from laying strains.3 As consumption grew and chicken became more popular, some enterprising businessmen started buying up their chicken suppliers — like the hatcheries, feed mills, slaughterhouses and packing plants — and integrated them under the umbrella of a single company, now referred to as an integrator.4

- Integrator

- A company that owns every link in the supply chain, such as hatcheries, feed mills, slaughterhouses and packing plants.

Owning every link in the supply chain allowed integrators to control price and quality from parent and egg genetics through shrink-wrapped grocery store packaging. The economies of scale, which the integrators have achieved, have driven the consumer price for chicken down dramatically.5 Americans now eat more than three times more chicken than we did in the 1960s, and we eat far more chicken than any other meat: in 1960, per capita consumption of chicken was not even one-third that of beef or pork; now it’s practically double.6

Poultry Industry Concentration

As the poultry industry has expanded, smaller companies have gone out of business or have been built around concentrating the raising of chickens (and the profits from their slaughter and sale) into fewer hands:

- From 1950 to 2017, the number of chickens produced annually in the U.S. increased by more than 1400 percent to more than 9 billion, while the number of farms producing them has dropped by 98 percent.78

- The top four U.S. poultry companies together controlled more than 60 percent of the broiler market in 2022, up from 17 percent in 1977.910This is a lucrative market: in 2021, Tyson (the top poultry integrator) earned $13 billion, Pilgrim’s Pride $13.8billion, and Perdue, $8 billion.111213

These companies have tremendous political power, as well as power over the people in their supply chain: the farmers who grow their chickens and the workers who process them.

The Problems With Conventional Poultry

Their small size has allowed chickens to fit well into an industrial system that seeks to maximize efficiencies with economies of scale. They have essentially become feathered widgets, produced in a mechanized assembly line like any other consumer product. But, of course, chickens are not widgets, but living creatures, and the people who work on the line are not machines.

Like in many industries seeking efficiencies, the chicken industry has created many externalities — costs that they don’t have to pay. These include financial, health and environmental costs for farmers, workers, the animals, the environment and surrounding communities.

“Chickenization:” Consolidation and Vertical Integration in the Chicken Industry

As poultry companies integrated the different parts of the supply chain into a single corporation, there was one part they didn’t buy up: the farms where the chickens spend six to seven weeks growing to slaughter weight. Don Tyson of Tyson Foods pioneered the integration model; he determined that the farm was the one place where capital investment and risk outweighed return.14 Therefore, it was not worth owning. So, how to grow the chickens?

The answer was to contract out the job to family farmers. The company retains ownership of the birds, but a farmer raises them on his or her farm for the weeks they take to grow to slaughter weight. Contracts are common in farming, and they can be useful to clarify business relationships and give farmers stability. But production contracts, the kind Tyson developed, instead turn farmers into serfs on their own land. The contracts, which farmers sign based on false promises of inflated returns, require the farmer to build chicken houses to company specifications and follow company protocol for care of the birds.15 It is common for a farmer to incur $1 million in debt to build their chicken houses, not counting the cost of the land. Meanwhile, the contracts only hold the company to a short-term commitment, often only from one flock to the next.

It is common for a farmer to incur $1 million in debt to build their chicken houses, not counting the cost of the land.

This arrangement — being on the hook for $1 million or more but only guaranteed one six-week flock of chickens at a time — puts the farmer in a precarious position, to say the least. While the farmer is paid based on how quickly the birds grow, the company controls all the variables, with no transparency. For example:

- The farmer is not allowed to weigh the company’s feed delivery him- or herself to ensure it is the weight the company reports.16

- The company may deliver a low-quality batch of feed or a flock of chicks that is sick or otherwise slow-growing.17 Ibid. 18 Despite it being a violation of USDA rules, the farmer may be prohibited from witnessing the company’s final weighing of the birds.19

- Companies can force growers into accepting new pay rates by pressuring indebted growers into signing new contracts.20

For these and other reasons, farmers have no way of knowing what they are working with, which makes it hard to trouble-shoot, make improvements, or even to be a farmer at all. This tightly, vertically integrated system has provided an unfortunate model for other meat production (like pork) and has come to be known as the “chickenization” of an industry.

The system is especially unfair, because farmers are paid based on how fast their chickens grow as against those of their neighbors, in a structure called the tournament. All the farmers in a region are ranked against each other for how efficiently they used company inputs to grow their chickens. The farmer in the middle of the group is paid the price per pound guaranteed in the contract; those who cost the company less are paid more, and those who cost the company more are paid less. The total cost per region for the company remains about the same from flock to flock, but a given farmer’s check can fluctuate wildly — one study showed that farmers at the bottom of a group were paid just 62 percent of those at the top.21 But how can farmers be judged on how well their chickens grow when they have little control over anything about how they grow?

- Tournament

- A structure in the chicken industry where farmers are paid based on how fast their chickens grow as against those of their neighbors.

Even worse, integrators can change the pay rates and pressure growers into signing new contracts that give them even less money. After Sanderson Farms, one of the country’s largest poultry processors, announced its acquisition by Cargill in 2021, they attempted to force growers to sign new contracts that cut already low pay by nine percent.22

While the farmers were successful in organizing against Sanderson’s pay cut, those who refused to sign the new contract started receiving smaller birds that had low reimbursement rates, along with other retaliatory measures. This isn’t uncommon in the tournament system: growers who complain about the system, organize with other growers, or do anything which the company might consider troublesome, risk retaliation. This can take the form of getting deliveries of poor-quality chicks or bad feed, dropping in the tournament rankings or having the company stop delivering flocks altogether.23 As variable as the income from raising flocks can be, in many cases it is all that keeps a farmer afloat financially. Being cut off can mean financial ruin. Even when getting regular deliveries of chicks, 50 to 75 percent of contract growers live below the poverty line, and two thirds have significant debt, which often ends in bankruptcy.24 In 2011, contract growers’ total debt nationwide amounted to $5.2 billion.25 Despite the crippling nature of this arrangement for contract growers, nearly 97 percent of the chicken we eat in the U.S. is raised on a farm under a production contract.26

Even worse, integrators can change the pay rates and pressure growers into signing new contracts that give them even less money. After Sanderson Farms, one of the country’s largest poultry processors, announced its acquisition by Cargill in 2021, they attempted to force growers to sign new contracts that cut already low pay by nine percent.27

While the farmers were successful in organizing against Sanderson’s pay cut, those who refused to sign the new contract started receiving smaller birds that had low reimbursement rates, along with other retaliatory measures. This isn’t uncommon in the tournament system: growers who complain about the system, organize with other growers, or do anything which the company might consider troublesome, risk retaliation. This can take the form of getting deliveries of poor-quality chicks or bad feed, dropping in the tournament rankings or having the company stop delivering flocks altogether.28 As variable as the income from raising flocks can be, in many cases it is all that keeps a farmer afloat financially. Being cut off can mean financial ruin. Even when getting regular deliveries of chicks, 50 to 75 percent of contract growers live below the poverty line, and two thirds have significant debt, which often ends in bankruptcy.29 In 2011, contract growers’ total debt nationwide amounted to $5.2 billion.30 Despite the crippling nature of this arrangement for contract growers, nearly 97 percent of the chicken we eat in the U.S. is raised on a farm under a production contract.31

Eric Hedrick, a contract chicken farmer in West Virginia, produces 1.3 million pounds of chicken every 35 days on his farm. As a contract farmer, once Eric has raised the chickens, the major food corporation that he is in contract with will collect, process and distribute the poultry.

Price Fixing

The fact that the tournament system isolates farmers and punishes them for communicating about prices they receive is ironic, considering the poultry industry itself is under investigation for unfair collusion to raise prices. Consolidation allows poultry processors an enormous amount of control over the market, and the prices of a few major players effectively determine prices for the entire industry. While colluding to set these prices is illegal in the US, chicken industry executives were found to have violated this rule from 2012-2019, an era they referred to as “chicken nirvana” because of their record-setting profits.32 In a rare move by the Department of Justice, ten executives from Pilgrim’s Pride, Perdue and others are facing criminal prosecution for the scandal.

The inflationary economic conditions of 2021 again brought consolidation and allegations of price fixing to the forefront. With more than half of rising grocery prices attributed to meat costs rising, the Biden Administration pointed the finger at the consolidated meat and poultry industries, alleging price fixing.33 While poultry producers argued that prices were increasing because of rising costs, their record-breaking profits indicate that they may be taking advantage of their consolidated position to fix prices artificially high.34

Worker Welfare

The human exploitation in the chicken industry follows the birds as they are brought to slaughter. Chicken “catchers” collect the birds from the growers’ barns at night when the animals are sleeping. Catching four in each hand, two nine-catcher crews can collect 75,000 birds in a night; earning just $2.25 for every thousand birds.35 At the poultry plant, the birds are killed, eviscerated and then hung on hooks on an automated “dis-assembly” line for workers to process. Poultry processing jobs are some of the most dangerous and poorly compensated in the country. Workers cut up thousands of birds every day, working in extreme conditions of heat or cold, with scalding water, chemicals and dangerous equipment.36 Respiratory issues, skin problems and falls are common.

Worker Welfare Info

- Chicken catchers earn just $2.25 for every 1,000 birds

- On an average day in the U.S. 27 poultry workers suffer work-related amputations and hospitalizations

- The poultry industry ranks 12th in severe injuries in a recent survey — more than saw milling, auto or steel.

The workplace is ruled by the line. The federally-allowed speed for the slaughter line has more than doubled in the last four decades, from 70 birds per minute in 1979 to 140 birds per minute today.37 Under the Trump administration, poultry plants were going to be granted the ability to move as high as 175 birds per minute, though the rule was withdrawn in 2021 by the Biden administration before it went into effect. Advocates for both worker and consumer safety applauded the move, though they say line speeds are still too fast for workers to do their jobs safely and work cleanly enough to minimize bacterial contamination concerns.38

Virtually nothing stops the movement of the line. Even bathroom breaks are discouraged or denied, and many workers resort to wearing diapers.39 Workers make the same cutting, pulling or hanging motions thousands of times a day; the repetitive motions cause crippling musculoskeletal injuries.40 Workers wield sharp knives and work with fast-moving heavy machinery. One study found that on an average day in the US, 27 poultry workers suffer work-related amputations or hospitalizations. In a recent survey of severe injuries reported at more than 14,000 companies, one poultry company and one meat-processing company rank fourth and sixth, respectively; and the poultry industry ranks 12th in severe injuries, overall, which is even higher than dangerous industries like saw milling, auto or steel.41

The Covid-19 pandemic brought even more danger to jobs in poultry processing and meatpacking, with more than 59,000 cases linked to plants as of September 2021.42 Poultry plants, with their cold air and crowded conditions, make ideal settings for uncontrolled viral spread.43 In spite of ongoing outbreaks, meatpackers lobbied the government to remain open, which they were granted in 2020 with minimal safety oversight. While many companies did adopt some prevention measures, they resisted the most necessary changes — like spacing workers at least six feet apart because they might slow down production, needlessly endangering workers.44

Animal Welfare

Industrially-raised broiler chickens are bred for speedy growth and raised in enormous barns with conditions further designed to make them grow as fast as possible.

How Genetic Technology Props Up the Industrial Chicken Industry

As chicken production was industrialized in the 1960s, scientists began to breed birds specialized for either meat or eggs.

- Layers, or hens that lay eggs, are bred for egg production. They are lean and tough, with little meat on their bones.

- Broilers, chickens grown for meat, are bred to grow quickly. They have enormous breasts to meet consumer demand for white meat.

Chickens are not genetically modified; this specialization is achieved through conventional breeding. (Read more about genetic engineering to understand the difference.) The chicken genome was sequenced in 2004, before any other livestock animal.45 This has allowed scientists to breed chickens to better grow in an industrialized setting. Genetic traits that animal scientists are trying to perfect, in order to make farming chickens more “effective” in a factory setting:

- Grow even more quickly with less feed.46

- Resist the diseases that occur when chickens are raised in factory farms, which often require the birds to be administered antibiotics and other drugs.47

- Produce less manure.48

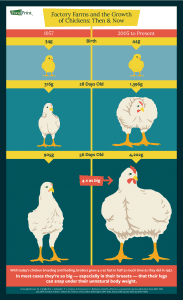

Broiler chickens grow extraordinarily quickly, not because they are fed growth hormones, but because of specialized breeding.49 Today, broilers grow to full slaughter weight of almost 6.2 pounds in six to seven weeks. In the early days of the industry, before 70 years of genetic manipulation, chickens took 12 weeks to reach market weight of three pounds.50

The overall trend has been a phenomenal increase in biological productivity. Between 1935 and 1995, the average market weight of commercial broilers increased by roughly 65 percent, while the time required to reach market weight declined by more than 60 percent and the feed required to produce a pound of broiler meat declined by 57 percent.51

In short, by the 1990s, a commercial broiler grew to almost twice the weight in less than half the time and on less than half the feed than it had in the 1930s.52

The birds’ muscles (which are the meat) grow much faster than their bones, so that in their last few weeks, their legs can no longer support their enormous breasts. Chickens can grow so quickly that they develop physical abnormalities, like deformed skeletons and “white striping disease,” where normally lean muscle becomes stripped with fatty tissue. A 2021 survey found white striping, which can increase meat’s fat content while decreasing protein, in 99 percent of sampled supermarket brands.53 For most of their lives, they sit, mostly immobile, in their own waste, which can lead to sores and ulcers on their skin, along with leg and foot problems.54 Their immune systems are underdeveloped, as well, making them more susceptible to illness.55

Consumer awareness about the problems with fast-growing birds has increased in recent years, leading to some companies experimenting with slower-growing birds that are healthier and can move around.56 These birds take more time to grow, and so their meat is somewhat more expensive. Many major companies have signed on to the Better Chicken Commitment, which stipulates that producers use slower grower breeds, but few major retailers or restaurant chains have adopted that part of the commitment, citing that they are unwilling to pass on those costs to their customers.57

INSIDE THE CHICKEN HOUSE

Conventional broiler chickens are never raised in cages, so the label “cage-free” on chicken meat is unnecessary and misleading. Like coconut water labeled “gluten-free” (coconuts do not contain gluten, so all coconut water is naturally gluten-free), the “cage-free” label touts a feature that is the norm as a selling point. This likely makes consumers think they are making a better choice (over the fictitious caged chickens), when they are simply getting the industry standard.

Instead of cages, 20,000 to 30,000 day-old chicks are delivered to a barn, where they are placed on a floor covered with wood shavings or another litter material.58 The tiny chicks quickly grow into the full space. In the last weeks of their short lives, broiler chickens have just over three-quarters of a square foot of living space.59

The litter, which is dirtied with droppings, spilled food and water, is not changed over the lifespan of a flock, and sometimes not even between flocks, which means that disease can be spread from one flock to the next.

High Ammonia Levels in Chicken Houses

Ammonia is an acrid and dangerous gas formed when chicken manure breaks down. Inside the chicken house, it can reach levels high enough to be harmful to the birds, especially when the litter gets wet or has not been changed between flocks.

Problems that elevated ammonia levels can cause include:

- Eye problems, including blindness

- Compromised respiratory systems which can lead to increased rates of E. coli infection

- Reduced weight gain, by as much as 25 percent60 Skin inflammation and infection on their feet and breasts (In addition to being painful for the birds, these sores can cause marks in the meat after processing.)61

Physical Modifications

Most broiler chickens are so young when they are slaughtered that they have not yet developed territorial instincts and are not aggressive towards each other. Many laying hens and turkeys have the tip of their beak cut or burned off (trimming) or even partially removed (debeaking) so that they do not cause injury when they peck at each other, but this procedure is not commonly done to broilers. It is done, however, to broiler breeders, the parents of the broiler chickens, who live for a year or two. Broiler-breeder roosters also sometimes have part of their foot or their spur removed to reduce risk of injury to the hen while mating.62

These procedures are extremely painful for the birds but are performed without anesthesia. The operations can lead to infection, improper healing and phantom pain. Beak trimming and debeaking can cause the bird problems with eating for the rest of its life.

Chicken Feed

Broiler feed is designed to fatten the birds as quickly as possible. It is made mostly of grain, especially corn and soybeans, supplemented with vitamins, minerals and enzymes.63

Under current U.S. farm policy, poultry integrators and other agribusiness companies can buy feed grains for less than what they cost to produce, while the government makes up some of the difference to the farmers. A 2006 study found that this “discount” saved the broiler chicken industry an average of $1.25 billion annually between 1997 and 2005 (the last time these numbers were crunched), as compared to whether the industry had to buy feed at the full cost of the grain.64 A farm policy that instead paid farmers a fair price for their goods would require companies to pay the full price for grain — and would likely make the days of cheap meat a thing of the past. (For more on farm policy and farmer prices, check out Political Economies of Food and Agriculture.)

What’s in that Chicken Feed?

Some companies label their chicken as “hormone-free,” but like “cage-free,” the label is unnecessary and misleading, because federal guidelines prohibit growth hormones or steroids being fed to broiler chickens. All chicken is hormone-free! Along the same lines, arsenic was a common additive to chicken feed for many years, but after a long fight by consumer groups, arsenic-based feed additives were withdrawn from the market in 2015.65

Chicken Feed Highlights

- All chicken is hormone-free — federal guidelines prohibit growth hormones or steroids.

- Arsenic-based feed additives were common until it was withdrawn from the market in 2015.

- There is no requirement that chicken be labeled with the kinds of drugs the bird was fed.

But other drugs are regularly given to industrially-raised chickens in their feed and water, including pesticides to control flies, beetles and parasites.66 One parasitic disease, coccidiosis, is so common in poultry that a dozen kinds of medication are approved for use in controlling it.67

For many years, chickens and other livestock were also routinely fed antibiotics, because the drugs act as growth promoters. While some large integrators have phased out the practice, some eggs and chicks (including some that go on to be sold as organic) are given an antibiotic at the hatchery during the vaccination process, and disease-preventing antibiotics are administered in the birds’ food or water throughout their lifetimes.6869 In 2017, the FDA ruled that antibiotics could no longer be used for growth promotion, but loopholes and lack of enforcement have meant that the rule is not as effective as is could be, but including preventative antibiotics in feed continues on some farms.70 Residues of drugs added to feed has sometimes been detected in the meat that gets sold to consumers — and yet there is no requirement that chicken meat be labeled with the kinds of drugs the bird was fed. The Food and Drug Administration guidance is that licensed antibiotics can be used as long as withdrawal times are met — at that point there is no requirement to label whether meat (or dairy) came from an animal that was ever given antibiotics. 71

Can Chickens Be Fed Sustainably?

From a sustainability perspective, feed is perhaps the most complex aspect of raising chickens. Even chickens raised eating bugs and grass on pasture do not get all their nutrients from foraging — the bulk of their diet comes from a corn and soybean-based feed mix. Unlike pastured beef, for example, which is raised in a closed loop where cows sustain themselves entirely on grass and in turn fertilize the soil with their manure, poultry are not self-sustaining, and instead require the external input of feed.

Environmentally, conventional feed grains are a high-cost input: they are genetically modified, grown with chemical pesticides and fertilizers that can run off into groundwater and depend on fossil fuels for planting, harvesting and transport. Organic feed grain, grown without chemical pesticides and fertilizer, has a much smaller foodprint, but comes with a considerably higher price tag at the feed store. Small-scale, pasture-based chicken farmers may not be able to afford the higher-priced organic feed, meaning that their otherwise environmentally-friendly operations rely in part on synthetics and fossil fuels to feed their birds.

However, while birds in confinement barns eat nothing but processed chicken feed, this makes up only a part of the diet for birds on pasture — and there are so many other benefits of raising chickens on pasture that it is certainly always the better option.

Food Safety and Public Health

Trillions of bacteria grow on and alongside the millions of chickens raised every year in crowded barns. Some of these bacteria are dangerous for humans, causing severe illness or even death — and they don’t stay in the barn, but hitch a ride out on blowing dust or on chicken carcasses, creating a public health threat in the form of disease outbreaks.

Foodborne Illness

Chicken is the cause of more foodborne disease and outbreak-related illnesses than any other food.72 Campylobactor bacteria causes 1.5 million illnesses in the U.S. annually, most of which is due to eating raw or undercooked poultry or something that came in contact with it.73 Salmonella bacteria are estimated to sicken 1.35 million people annually, leading to 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths.74 Most salmonella infections are from tainted food. Cereals, raw vegetables, prepared foods and other items have caused outbreaks in recent years, but the bacteria is most commonly associated with poultry. Symptoms of both campylobacter and salmonella poisoning include diarrhea, fever and abdominal cramps. Most people recover quickly, but those with compromised immune systems are at risk of more severe and lasting symptoms.

Both of these bacteria contaminate meat during slaughter and processing, when waste can easily come in contact with meat.75 According to recent USDA data, 35 percent of the country’s biggest chicken slaughter and processing facilities fail to meet safety standards to prevent salmonella contamination on chicken parts.76 The USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service mechanisms for enforcing these safety standards are weak, allowing bad business behavior to continue. For example, ten of 11 plants run by the third largest chicken company in the U.S. are out of compliance with USDA food safety standards.77 Producing millions of pounds of chicken in centralized facilities means that if one processing plant has an outbreak of campylobacter or salmonella, contaminated chicken parts rapidly wind up in grocery stores around the country.

By contrast, governments in some European countries have taken measures aimed at curbing salmonella at every link in the production chain, from carefully monitoring breeder stock for the bacteria to sanitary feed handling procedures to workers changing clothes between rooms in order not to spread any potential bacteria. As a result, Sweden and Denmark have virtually eliminated salmonella from poultry products.78 And while chickens raised on pasture can also carry these bacteria, the sunlight, fresh air and increased space these birds enjoy — along with stronger immune systems — makes them healthier.79 The American chicken industry has historically resisted making these changes because of their cost, passing on the burden of food safety to consumers. With more than 15 percent of chicken samples leaving a production plant allowed to test positive for some kind of salmonella, consumer safety advocates are petitioning the USDA to classify the most dangerous strains of the bacteria as an “adulterant,” making them unacceptable in any quantity.8081But so far, the industry has argued this is an unrealistic standard, despite evidence that targeted elimination of salmonella strains is possible with more careful production and more stringent testing.

Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

As alarming as the prevalence of salmonella contamination is, it’s even more alarming that one in five strains of salmonella found on grocery store chicken were resistant to one of the most common antibiotics used to treat the bacteria.82

Antibiotics are medically essential drugs, responsible for saving millions of lives since they were developed. Overuse of these drugs to promote growth or prevent disease in chickens and other livestock leads to evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, rendering the drugs obsolete. And they are, indeed, overused: 65 percent of all medically important antibiotics sold in 2019 were fed to farm animals.83 When bacteria are continually exposed to small doses of an antibiotic, those resistant to the drug survive and reproduce while the rest die off, resulting in a new bacteria population that is resistant to the antibiotic.84 Bacteria can also develop resistance through genetic mutation; other kinds of mutations can transfer resistance among species. This means, for example, that bacteria resistant to an antibiotic in birds can mutate so that it can infect humans as well.

20%

Strains of salmonella found on grocery store chicken that were resistant to one of the most common antibiotics used to treat the bacteria.

The World Health Organization and many other public health bodies consider antibiotic resistance a global public health crisis. More than half of some bacteria groups in some countries are currently resistant to antibiotics.85 In the US, at least 2.8 million people are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, killing 35,000.86

Recognizing these risks, along with consumer demand for antibiotic-free chicken, several efforts are underway to reduce or eliminate antibiotics in chicken production.87 The European Union banned the use of antibiotics for growth promotion in 2006 and some countries have placed restrictions on the use of some antibiotics that are medically important in humans, for disease prevention as well. The U.S. FDA also banned their use for growth promotion in 2017, and as of 2021, almost all medically important antibiotics must be used under the supervision of a veterinarian.88 While these rules are intended to curb overuse, but enforcement is lax, making it relatively simple for growers to skirt the rules.89 However, antibiotic use in U.S. chicken has fallen considerably, with a more than 72 percent reduction in the use of medically important antibiotics from 2016 to 2020.90

Use of non-medically important antibiotics remains high in chickens, however, which still carries risks for the development of antibiotic resistant infections in the animals.91

Poultry companies in the Netherlands and elsewhere are experimenting with different kinds of chicken barns to reduce stress, improve survival and eliminate all antibiotic use in their chickens.92 In the US, several major fast food brands have made commitments to reducing use of antibiotics in their chicken supply chains, and one of the top four chicken companies eliminated routine use of all antibiotics used to treat both humans and animals in 2016.93 These changes have added up quickly, with nearly half of all chickens produced without any antibiotics throughout their lifetime, far outstripping other sectors of the livestock industry.94

It should be noted, however, that while these improvements often include cleaner and somewhat more spacious conditions, most chickens raised without antibiotics are housed in the same industrialized, confined system and with many of the same problems. “Raised without antibiotics” is a baseline label indicating a better chicken, not the best.

Bird Flu

Avian influenza, or bird flu, is not just an animal health issue: some strains have evolved to spread to humans and can be deadly. Bird flu originates in wild waterfowl and can be transmitted to domesticated poultry or other animals who come in contact with infected birds. Poorly ventilated, crowded, dirty confinement poultry operations provide perfect conditions for bird flu to quickly mutate and spread.95

So far, the varieties of bird flu that have spread to humans have only done so through direct contact with infected birds. Strains of the virus that can pass from human to human are extremely rare, but the Centers for Disease Control and other global health organizations that monitor bird flu outbreaks warn that the virus could mutate into a dangerous strain able to pass between humans.96

Impact on Environment and the Community

Use of Water Resources

Chicken has a relatively small water footprint, as compared with other livestock, because of their mass production and small size.97 Conventional chicken production requires less than one-third the water needed by beef and about three-quarters that of pork.98

Chicken processing, however, uses a great deal of water: after the bird is killed and its feathers are removed, it needs to be quickly chilled. In the US, most processors do this by submerging the carcass in ice water, often treated with antimicrobial agents like chlorine or hydrogen peroxide. The flesh absorbs some of the water, as well as whatever else was in the water. Some companies now air-chill the birds instead, blasting them with cold air instead of water. Air chilling takes longer, adding cost to the meat — but it also saves half a gallon of water per bird. This could work out to a 4.5 billion-gallon savings if all chicken were processed that way.99

Impacts on Water Quality

In the “Broiler Belt,” the Southern U.S. states where poultry production is concentrated, water pollution is rampant.

Chicken manure is especially high in both phosphorus and nitrogen, which are valuable fertilizers. Some farmers with diversified farm operations use chicken litter (the combination of the birds’ bedding and the manure and other waste products in it) to fertilize their crops or sell it for added income. But for many farmers, the only option to get rid of the huge quantities of manure is to spread it on cropland — and there is so much of it that far more is spread than the land can absorb, and often more than is legally allowed.100 When it rains, the excess nutrients and drug residues run off the fields into streams and rivers and seep into groundwater.

In places like the Eastern Shore of Maryland, home to thousands of broiler houses, rivers have phosphorous concentrations among the highest in the nation — linked to the 5.7 billion pounds of manure produced by the area’s chicken industry.101The Chesapeake Bay, which gets runoff from the many chicken houses on the Delmarva Peninsula, is dangerously polluted and has regular toxic algae blooms and dead zones caused by excess nitrogen.102

Ammonia, which is highly concentrated in chicken houses and harmful for the chickens, adds to the problem of water pollution when it is blown out of the barns. Airborne ammonia settles onto the ground as nitrogen, adding to the already-significant nutrient runoff from manure.103

Water pollution from industrial chicken production affects human health and recreation; the environment; and the industries (like fishing) that depend on clean water. Excess nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, and the algal blooms they cause, result in many environmental problems, from loss of aquatic life and habitats, to shellfish contamination, to seasonal dead zones.104 Beaches may close from algal blooms, while excessive nutrient runoff in waterways can even impact drinking water supplies and cause severe health problems, such as blue baby syndrome (which results from excess nitrates in drinking water).105106

The Impact on Air Quality

Ammonia is harmful for the community, too. Even dispersed into the surrounding air, the odor of ammonia can be overwhelming, leading to reduced property values and depressed tourism.107

The fans also blow out dust and dried manure, which may contain salmonella or other harmful bacteria. People who live near poultry barns can develop respiratory health problems, as well as increased rates of illness from antibiotic-resistant bacteria.108

People living near these farms — which are increasingly being built in residential communities in places like North and South Carolina, for example — report experiencing respiratory problems from the ammonia and litter particles, and unpleasant daily life resulting from the odors and flies. Communities have sought restrictions (and sometimes initiated lawsuits) to curb the growth of these facilities. But lawmakers, often backed by big chicken companies, have begun to propose legislation to curb the efforts of community members.109

Pollution, Lawsuits and Regulation in the Chicken Industry

As poultry CAFOs and chicken processors ramp up production in many areas of the US, lax regulations and government inaction have meant that local residents are increasingly using lawsuits to take action to protect local waterways, drinking water and air from the pollution caused by raising chickens in confinement, along with slaughtering and processing the birds.

Concerningly, local and state lawmakers, often working with poultry companies, have countered this movement by passing laws that make it easier for CAFOs and processors to operate in local communities, despite community opposition. CAFO operators often also expect local tax breaks and other public subsidies to build their operations.

Here’s a recent example:

- In 2017, Tyson tried to build a new chicken plant in two different communities in Kansas. Community opposition, including objections “to the potential smells, traffic, pollution and social impacts that can go along with large-scale chicken processing,” caused the plans to fall through.110 Community concerns included that the proposed plant would cause odors strong enough to impact enrollment at Kansas University and damage the local watershed, including the Kansas River.111 However, in 2018, the Kansas state legislature passed a bill that made it easier for chicken factory farms to be sited near homes – with the “desire to bring large-scale poultry producers and the jobs they can offer to the state” driving legislative support for the bill, even with the history of community opposition to these factory farms.112 After the outcry in Kansas, Tyson decided to move the plant from Kansas to Tennessee, which passed a state law in 2018 that effectively exempts chicken factory farms from having to get state water quality permits.113114

The Promise of Pastured Poultry

Instead of being grown in a factory, chickens can be raised on pasture, with plenty of space to move around, a diet of foraged insects and grass to supplement their feed and a genetic make-up that keeps them growing at a healthy rate — all of which makes for more delicious meat.

Chickens that move more have tastier meat, too, because the muscle fiber gives the meat a better texture.

Better Animal Welfare

Overall, chickens raised on pasture are healthier. They have a more diverse diet, and the combination of sun, fresh air and more robust genetics makes them better able to fight off disease. Pastured birds need to be able to move around to forage, so they are not the nearly-immobile breeds raised in confinement operations. That said, most pastured chickens are fast-growing breeds, but slower-growing breeds, including heritage breeds, are increasingly available.

Chickens that move more have tastier meat, too, because the muscle fiber gives the meat a better texture.115 Companies developing slower-growing breeds are also touting the improved taste that comes from slower growth, and aficionados of heritage breeds swear by the flavor of those birds.116 117

Better Waste Management

When their numbers are low enough that their waste does not overwhelm what the ground can absorb, chickens can be excellent for soil health. In a pasture rotation with other livestock, like cattle, they eat larvae of pests in the cow’s manure and spread the dung into the soil with their scratching. Chickens who spend their days outdoors do not build up noxious levels of ammonia or other gasses; therefore, the animals are healthier, and so are neighboring communities. Healthier in this case is defined as not needing to be given preventative antibiotics or other drugs.

More Farmer and Worker Autonomy

Pastured chickens are generally raised by farmers with some degree of autonomy over their operations, rather than those under unfair contracts with a multinational corporation. Chickens are also usually only one part of a diversified farm operation. These farmers may well be struggling financially (see points below on costs), but if they are losing money from chicken sales, they likely have other parts of the farm business to fall back on.

Depending on the size of the farm, pastured poultry may be processed on the farm or in a small-scale processing facility. These plants may have better working conditions and be less exploitative than the operations that process thousands of birds a day.

The Challenges of Pastured Poultry

The cost of producing chicken raised on pasture is considerably higher than that of chicken raised in confinement as fast-growing broilers. Some farmers raising other livestock may keep chickens too, primarily for their soil-building benefits; but they may consider the income from other livestock sales as subsidizing the chicken side of the business.118 Consumers who may be used to purchasing inexpensive chicken may balk at the price difference between conventional chicken and healthier alternatives, whether from a large organic brand or from the farmers’ market, even when those prices may reflect only what a farmer needs, simply to break even.

For those who can afford to pay a few extra dollars for a pound of chicken, consider making the switch to pasture-raised and thinking of it as an investment in growing a healthier food system for all.

Beyond the farmers’ market and grocery store aisles, there are organizations fighting to limit the environmental impacts of large chicken facilities and support laws that will make it more viable to produce chickens in a way that is better for animals and the environment.

What Do Chicken Labels Mean?

People looking for a simple label to help guide them to chicken that has been produced in a sustainable way might be disappointed to find out that chicken labels can be complicated. There is no one label for chicken that tells you about both animal and human welfare. There are great labels that certify environmental and animal welfare standards, though they are not always widely available. As for finding chicken raised by independent farmers who are paid a living wage and processed by workers who are treated well and compensated fairly, no single label addresses all of these concerns. Consumers must decide which factors are most important to them.

But there are a few labels that companies slap on chicken that are downright meaningless. Chickens raised for meat are never raised in cages or given hormones — so “cage-free” and “hormone-free” chicken meat doesn’t mean anything. Some words like “natural” and “humane” have no legal definition or are not verified by third-party inspectors and can also be ignored.

“Air-chilled” means that the parts were cooled with air rather than in a water bath. Therefore, much less water was used in processing the bird, which is better for the environment. The meat itself has less added water and is free of whatever chemicals are used in those baths. (See above for more on air chilling.)

“Raised without antibiotics,” “no antibiotics ever,” and “never given antibiotics” indicate that no antibiotics of any kind were used in the raising of the animal.

As for overall labels, look for these:

Animal Welfare Approved

Animal Welfare Approved has among the most stringent standards for animal welfare including comprehensive standards for breed type (including growth rates), pasture-based raising, transport and slaughter.

USDA Organic

USDA Organic has among the strongest standards for environmental sustainability including prohibiting synthetic fertilizers and industrial pesticides. Animal feed must be 100 percent organically produced and without animal byproducts or daily drugs. GMOs are prohibited (though testing is not required). However, there are limited standards on access to pasture for organic birds. For example, no minimum outdoor pasture area that is mandated.

Demeter Certified Biodynamic

Demeter Certified Biodynamic is an environmental sustainability label that goes even beyond organic standards. It would be a top pick if it were more widely available. It also has basic animal welfare standards.

Let's Fix This: Creating a System That Makes Sense

The broiler chicken industry is complicated. To move towards a system where chicken is humanely raised by farmers and workers who are fairly treated, we need to both push for better options in the current system (like birds raised without antibiotics) and support efforts to build a more pasture-based alternative.

1. Eat less chicken

The chicken industry has developed in such a way that it must produce as much chicken as cheaply as possible, because demand is high. Though it may be a small step, you can lower that demand simply by consuming less chicken. Try Meatless Mondays, or eat chicken only with labels you trust. That might mean skipping the chicken when you go out to eat — go vegetarian for that meal, instead.

2. Look for labels that mean something

Buying chicken with meaningful labels is a great place to start. Look for:

- Animal Welfare Approved

- USDA Organic

- Demeter Certified Biodynamic

- Global Animal Partnership Steps 3, 4, 5 and Step 5+

3. Seek out farms raising pastured chicken

You’ll find these at your local farmers’ markets and at food co-ops that vet their growers. Sometimes these farms welcome visitors. See for yourself where your chicken comes from.

4. Stand up for chicken growers and workers

While working towards a wholly different model of chicken production, we’ve got to take care of the people toiling in the current system. You can support groups who are working to improve conditions for chicken growers, like RAFI-USA, and poultry plant workers, like Northwest Arkansas Workers Justice Center.

5. Use institutional power

Institutions like schools and hospitals spend millions of dollars on food purchases annually; shifting that buying power to organic, local, humanely-raised, pastured or other better practices can make a big difference. Get involved with an organization that is working with institutions to make that change — try your local school, the National Farm to School Network, the Good Food Purchasing Program or Health Care Without Harm.

6. Fight for strong manure management laws and state and local policy change around factory farms

If you live in a rural state that is trying to attract more concentrated chicken farms, pay attention to how state laws on animal waste may be changing — and get involved with efforts to maintain existing regulations. These are generally driven by corporate interests and big farm groups claiming to speak for all farmers. However, there are organizations of independent family farmers, partnered with environmental, public health and other groups, and together they fight these bills. Support local and national policies and politicians working more broadly towards food system reform.

7. Advocate for meaningful labels

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s labeling standards should be improved to reflect what consumers think they mean. Creating verifiable standards for “free-range,” “pastured” or “pasture-raised” labels would help consumers make informed choices when buying chicken.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s labeling standards should be improved to reflect what consumers think they mean. Creating verifiable standards for “free-range,” “pastured” or “pasture-raised” labels would help consumers make informed choices when buying chicken.

Follow us on Twitter for the latest news about policy and regulation developments and to learn about current campaigns to change the FoodPrint of Chicken.

Conclusion

Due to the cost, pastured poultry raised in small flocks by independent farmers is mostly available at farmers’ markets and through other similar direct marketing.

But the good news is that in recent years, the public’s desire to learn more about where our food comes from has made a real difference. Consumer demand for options like antibiotic-free chicken has led stores and restaurants to make commitments to provide these choices, which has in turn forced the chicken industry to change in this area. In other important areas, however, the conventional, industrial chicken industry is just as bad as it has ever been; our food choices and our voices raised to change local and national policy can push for even more sweeping changes in the system.

As with all food choices, there are always trade offs — there is no ideal chicken. But there are lots of better options. And we’re not done yet: advocacy organizations, consumers, farmers, policymakers, companies and many others are working every day for change. Together, we can shift the poultry industry toward being more humane and fairer for all.

Researched and written by:

Hide References

- “Big Chicken: Pollution and Industrial Poultry Production in America.” The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Pew Charitable Trusts, 26 July 2011, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2011/07/26/big-chicken-pollution-and-industrial-poultry-production-in-america.

- Boyd, William. “Chapter 8: Agro-Industrial Just-in Time: The Chicken Industry and Postwar American Capitalism.” Globalising Food: Agrarian Questions and Global Restructuring, edited by David Goodman and Michael Watts, Routledge, London, 1997, p. 33.

- Ibid.

- “Vertical Integration.” National Chicken Council, 2022, https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/industry-issues/vertical-integration/.

- “Wholesale and Retail Prices for Chicken, Beef, and Pork.” National Chicken Council, 22 Mar. 2021, https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/wholesale-and-retail-prices-for-chicken-beef-and-pork/.

- “Per Capita Consumption of Poultry and Livestock, 1965 to Forecast 2022, in Pounds.” National Chicken Council, 20 Dec. 2021, https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/per-capita-consumption-of-poultry-and-livestock-1965-to-estimated-2012-in-pounds/.

- “Big Chicken: Pollution and Industrial Poultry Production in America.” The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Pew Charitable Trusts, 26 July 2011, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2011/07/26/big-chicken-pollution-and-industrial-poultry-production-in-america.

- “ CHICKENS, BROILERS – OPERATIONS WITH SALES 2017.” Quick Stats, USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/4C73525E-1410-3E59-B8B2-22899A126D31.

- Sorvino, Chloe. “Higher Chicken Prices Expected after $4.5 Billion Poultry Merger Wins U.S. Approvala.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 5 Aug. 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/chloesorvino/2022/08/05/higher-chicken-prices-expected-after-45-billion-poultry-merger-wins-us-approval/?sh=768a94d967b9.

- Nelson, Willie, and Marcy Kaptur. “U.S. Poultry Farmers’ Rights Are under Siege.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 7 July 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/us-poultry-farmers-rights-are-under-siege/2015/07/07/cce6ad60-23fc-11e5-b77f-eb13a215f593_story.html.

- “Tyson Foods Reports Fourth Quarter 2021 Results.” Tyson Foods, 15 Nov. 2021, https://www.tysonfoods.com/news/news-releases/2021/11/tyson-foods-reports-fourth-quarter-2021-results.

- “Pilgrim’s Pride (PPC).” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 21 Dec. 2021, https://www.forbes.com/companies/pilgrims-pride/?sh=2917c245366b.

- “Perdue Farms.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 23 Nov. 2021, https://www.forbes.com/companies/perdue/?sh=6dda2b68c7ca.

- Leonard, Christopher. “The Ugly Economics of Chicken.” The Week, The Week, 11 Jan. 2015, https://theweek.com/articles/447911/ugly-economics-chicken.

- “Under Contract: Farmers and the Fine Print.” RAFI USA, Rural Advancement Foundation International , 12 Apr. 2017, https://rafiusa.org/blog/undercontract/.

- Lee, Sally. “Under Contract: Comparative and Relative Risk in Livestock Production Contracts.” Humboldt University Master’s Thesis, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://lib.ugent.be/fulltxt/RUG01/002/217/302/RUG01-002217302_2015_0001_AC.pdf

- Moodie, Alison. “Fowl play: the chicken farmers being bullied by big poultry.” The Guardian, April 22, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2017/apr/22/chicken-farmers-big-poultry-rules

- Ibid.

- Brown, Marcia. “Facing a Merger and a Pay Cut, Chicken Farmers Push Back.” Food and Environment Reporting Network, 4 Oct. 2021, https://thefern.org/2021/10/facing-a-merger-and-a-pay-cut-chicken-farmers-push-back/.

- MacDonald, James M. “Technology, Organization, and Financial Performance in U.S. Broiler Production.” USDA ERS, USDA Economic Research Service, June 2014, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=43872.

- Brown, Marcia. “Facing a Merger and a Pay Cut, Chicken Farmers Push Back.” Food and Environment Reporting Network, 4 Oct. 2021, https://thefern.org/2021/10/facing-a-merger-and-a-pay-cut-chicken-farmers-push-back/.

- “Under Contract: Farmers and the Fine Print.” RAFI USA, Rural Advancement Foundation International , 12 Apr. 2017, https://rafiusa.org/blog/undercontract/.

- “John Oliver Viewer’s Guide – Rural Advancement Foundation International.” RAFI USA, Rural Advancement Foundation International , 11 June 2015, https://rafiusa.org/blog/john-oliver-viewers-guide.

- MacDonald, James M. “Technology, Organization, and Financial Performance in U.S. Broiler Production.” USDA ERS, USDA Economic Research Service, June 2014, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=43872.

- Ibid.

- Brown, Marcia. “Facing a Merger and a Pay Cut, Chicken Farmers Push Back.” Food and Environment Reporting Network, 4 Oct. 2021, https://thefern.org/2021/10/facing-a-merger-and-a-pay-cut-chicken-farmers-push-back/.

- “Under Contract: Farmers and the Fine Print.” RAFI USA, Rural Advancement Foundation International , 12 Apr. 2017, https://rafiusa.org/blog/undercontract/.

- “John Oliver Viewer’s Guide – Rural Advancement Foundation International.” RAFI USA, Rural Advancement Foundation International , 11 June 2015, https://rafiusa.org/blog/john-oliver-viewers-guide.

- MacDonald, James M. “Technology, Organization, and Financial Performance in U.S. Broiler Production.” USDA ERS, USDA Economic Research Service, June 2014, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=43872.

- Ibid.

- Van Voris, Bob. “‘The Fix Was In’: DOJ Takes on Chicken Insiders in Price-Fixing Trial.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 27 Oct. 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-27/-chicken-nirvana-shows-insiders-raised-prices-on-kfc-doj-says.

- Deese, Brian, et al. “Addressing Concentration in the Meat-Processing Industry to Lower Food Prices for American Families.” The White House, The United States Government, 8 Sept. 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/blog/2021/09/08/addressing-concentration-in-the-meat-processing-industry-to-lower-food-prices-for-american-families/.

- Abbott, Chuck. “White House Points Inflation Finger at Meatpackers.” Successful Farming, Successful Farming, 13 Dec. 2021, https://www.agriculture.com/news/business/white-house-points-inflation-finger-at-meatpackers.

- Grabell, Michael. “Exploitation and Abuse at the Chicken Plant.” The New Yorker, 1 May 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/05/08/exploitation-and-abuse-at-the-chicken-plant.

- Press, Eyal. “Jessica Robertson Got Sick Working as an Inspector at a Poultry Plant. Now She’s Speaking out to Defend Workers Exposed to Chemicals.” The Intercept, The Intercept, 19 July 2018, https://theintercept.com/2018/07/19/moroni-utah-turkey-farm-workers-norbest/.

- Ronholm, Brian. “Eschewing Obfuscation on Poultry Slaughter Line Speed.” Food Safety News, Marler Clark, 13 Jan. 2018, https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2018/01/eschewing-obfuscation-on-poultry-slaughter-line-speed/.

- “Biden Repeals USDA Proposal to Increase Poultry-Processing Line Speeds.” Safety+Health Magazine, Safety+Health Magazine, 1 Feb. 2021, https://www.safetyandhealthmagazine.com/articles/20794-biden-repeals-usda-proposal-to-increase-poultry-processing-line-speeds.

- “Lives on the Line: The Human Cost of Cheap Chicken.” Oxfam, Oxfam America, 26 Oct. 2015, https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/lives-on-the-line/.

- Ibid.

- “Report: 27 Workers a Day Suffer Amputation or Hospitalization, Acc. to OSHA Severe Injury Data from 29 States.” National Employment Law Project, 27 Apr. 2017, https://www.nelp.org/news-releases/osha-severe-injury-data-report/.

- Douglas, Leah. “Mapping Covid-19 Outbreaks in the Food System.” Food and Environment Reporting Network, 8 Sept. 2021, https://thefern.org/2020/04/mapping-covid-19-in-meat-and-food-processing-plants/.

- Young, Jeremy. “How Us Poultry Plants Became Deadly Covid-19 Hotspots.” How US Poultry Plants Became Deadly COVID-19 Hotspots | Al Jazeera English, Al Jazeera, 21 Oct. 2020, https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2020/covid-19-in-us-poultry-plants/index.html.

- Ibid.

- Bunge, Jacob. “How to Satisfy the World’s Surging Appetite for Meat.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 4 Dec. 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-to-satisfy-the-worlds-surging-appetite-for-meat-1449238059?mod=fromImagePromo.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Held, Lisa. “Who Gets to Define Heritage Breed Chickens?” Civil Eats, 6 June 2018, https://civileats.com/2018/06/06/who-gets-to-define-heritage-chickens/.

- “U.S. Broiler Performance.” National Chicken Council, 15 Feb. 2022, https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/u-s-broiler-performance/.

- Boyd, William. “Making Meat: Science, Technology, and American Poultry Production.” Technology and Culture, vol. 42, no. 4, 2001, pp. 631–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25147798.

- Ibid.

- Pollard, Amelia. “White Striping Disease Hits 99% of U.S. Supermarket Chicken, Study Finds.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 19 Sept. 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-09-20/white-striping-hits-99-of-u-s-supermarket-chicken-study-finds.

- Strom, Stephanie. “A Chicken That Grows Slower and Tastes Better.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 May 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/01/dining/chicken-perdue-slow-growth-breed.html.

- Reddy, M., and A. K. Panda. “Boosting the Chicks Immune System through Early Nutrition.” WATTPoultry, WATTPoultry, 30 June 2009, https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/662-boosting-the-chicks-immune-system-through-early-nutrition.

- Strom, Stephanie. “A Chicken That Grows Slower and Tastes Better.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 May 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/01/dining/chicken-perdue-slow-growth-breed.html.

- Held, Lisa. “Fast Food and Grocery Giants Promise to Sell ‘Better’ Chicken-Is It Enough?” Civil Eats, 21 Oct. 2021, https://civileats.com/2021/10/14/better-chicken-commitment-fast-food-grocery-giants-promise-sell-better-chicken-is-it-enough-perdue-tyson-cage-free-labeling/.

- “Space & Housing: Are Chickens Crammed in Houses? Do Chickens Have Enough Space to Move?” Chicken Check In, National Chicken Council, 2020, https://www.chickencheck.in/faq/space-chicken-houses/.

- “National Chicken Council Animal Welfare Guidelines and Audit Checklist.” National Chicken Council, National Chicken Council, 2 Feb. 2017, https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/NCC-Welfare-Guidelines-Broilers.pdf.

- Aziz, Tahseen. “Harmful Effects of Ammonia on Birds.” Poultry World, 19 Apr. 2021, https://www.poultryworld.net/Breeders/Health/2010/10/Harmful-effects-of-ammonia-on-birds-WP008071W/.

- Oviedo-Rondón, Edgar O. “Tips to Reduce Dermatitis in Broilers.” The Poultry Site, Global Ag Media, 29 Oct. 2010, https://www.thepoultrysite.com/articles/1841/tips-to-reduce-dermatitis-in-broilers/.

- “An HSI Report: Human Health Implications of Intensive Poultry Production and Avian Influenza.” HSI, Humane Society International, Mar. 2008, https://www.hsi.org/assets/pdfs/hsi-fa-white-papers/human_health_implications_of.pdf.

- Zhai, Wei. “Why the Rapid Growth Rate in Today’s Chickens.” The Poultry Site, Global Ag Media, 10 Dec. 2012, https://www.thepoultrysite.com/articles/2699/why-the-rapid-growth-rate-in-todays-chickens/.

- Wise, Timothy, and Elanor Starmer. “Feeding at the Trough: Industrial Livestock Firms Saved $35 Billion from Low Feed Prices.” Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, 1 Dec. 2007, https://www.iatp.org/documents/feeding-trough-industrial-livestock-firms-saved-35-billion-low-feed-prices.

- “Arsenic-Based Animal Drugs and Poultry.” Center for Veterinary Medicine , U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 29 Apr. 2022, https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/product-safety-information/arsenic-based-animal-drugs-and-poultry

- Jacon, Jacquie. “Drugs Approved for Use in Conventional Poultry Production.” Extension Foundation , USDA NIFA , 4 Nov. 2015, https://poultry.extension.org/articles/feeds-and-feeding-of-poultry/feed-additives-for-poultry/drugs-approved-for-use-in-conventional-poultry-production/.

- Ibid.

- Charles, Dan. “Perdue Says Its Hatching Chicks Are off Antibiotics.” NPR, NPR, 3 Sept. 2014, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/09/03/345315380/perdue-says-its-hatching-chicks-are-off-antibiotics.

- Philpott, Tom. “Wait, We Inject Antibiotics into Eggs for Organic Chicken?!” Mother Jones, 15 Jan. 2014, https://www.motherjones.com/food/2014/01/organic-chicken-and-egg-antibiotics-edition/.

- McKenna, Maryn. “FDA Finally Cuts Antibiotic Use in Livestock.” Newsweek, Newsweek, 13 Jan. 2017, https://www.newsweek.com/after-years-debate-fda-curtails-antibiotic-use-livestock-542428.

- Medicine, Center for Veterinary. “Adequate Records Help Prevent Drug Residues and Ensure Food Safety.” FDA Animal Health Literacy , U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1 Mar. 2023, https://www.fda.gov/animalveterinary/resourcesforyou/animalhealthliteracy/ucm314503.htm.

- Dewey-Mattia, Daniel, et al. “Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks – United States, 2009–2015.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 27 July 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/ss/ss6710a1.htm.

- “Campylobacter (Campylobacteriosis).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 14 Apr. 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/campylobacter/index.html.

- “Salmonella Homepage.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 30 Mar. 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/index.html.

- Nicorici, Gheorghe, and Hamid B Ghoddusi. “Prevalence of Campylobacter Contamination in Raw Chicken and Chicken Liver at Retail.” Food Safety Magazine, BNP Media, 1 Apr. 2017, https://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/magazine-archive1/aprilmay-2017/prevalence-of-campylobacter-contamination-in-raw-chicken-and-chicken-liver-at-retail/.

- Philpott, Tom. “Your Chicken’s Salmonella Problem Is Worse than You Think.” Mother Jones, 5 Aug. 2018, https://www.motherjones.com/food/2018/08/chicken-salmonella-federal-inspection-slaughterhouse-sanderson-illness-usda/.

- Ibid.

- Terry, Lynne. “Contaminated Chicken: How Denmark Solved Its Salmonella Problem.” OregonLive, The Oregonian, 19 Mar. 2014, https://www.oregonlive.com/health/index.ssf/2014/03/contaminated_chicken_denmark.html.

- Spencer, Terrell. “Why Raise Poultry on Pasture?” The Poultry Site, Global Ag Media, 21 Sept. 2012, https://www.thepoultrysite.com/articles/2593/why-raise-poultry-on-pasture/.

- Carr, Teresa. “Why Salmonella Is a Food Poisoning Killer That Won’t Go Away in the US.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 10 Aug. 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/aug/10/why-salmonella-is-a-food-poisoning-killer-that-wont-go-away-in-the-us.

- Bustillo, Ximena. “The Bubbling Salmonella Food Fight.” POLITICO, 22 Nov. 2021, https://www.politico.com/newsletters/weekly-agriculture/2021/11/22/the-bubbling-salmonella-food-fight-799026.

- Meadows, Aurora. “Supermarket Meat Still Superbugged, Federal Data Show.” EWG, Environmental Working Group, 18 June 2018, https://www.ewg.org/research/superbugs/.

- McKenna, Maryn. “Antibiotic Use in U.S. Farm Animals Was Falling. Now It’s Not.” Wired, Conde Nast, 14 Dec. 2021, https://www.wired.com/story/antibiotic-use-in-us-farm-animals-was-falling-now-its-not/.

- “Antimicrobial Resistance.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 17 Nov. 2021, https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/.

- “Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 1 Apr. 2014, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564748.

- 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 23 Nov. 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html.

- Philpott, Tom. “How Factory Farms Play Chicken with Antibiotics.” Mother Jones, 16 May 2016, https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2016/05/perdue-antibiotic-free-chicken-meat-resistance/.

- FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine. “FDA Finalizes Guidance to Bring Remaining Approved Over-The-Counter Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs Used for Animals Under Veterinary Oversight.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, FDA, 10 June 2021, https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/cvm-updates/fda-finalizes-guidance-bring-remaining-approved-over-counter-medically-important-antimicrobial-drugs

- McKenna, Maryn. “FDA Finally Cuts Antibiotic Use in Livestock.” Newsweek, Newsweek, 13 Jan. 2017, https://www.newsweek.com/after-years-debate-fda-curtails-antibiotic-use-livestock-542428.

- FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine. “FDA 2020 Report on Antimicrobial Sales for Food-Producing Animals.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, FDA, Dec. 2021, https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/cvm-updates/fda-releases-annual-summary-report-antimicrobials-sold-or-distributed-2020-use-food-producing.

- Ibid.

- McKenna, Maryn. “The Matrix for Chicken May Be the Future of Meat.” Slate , Slate Magazine, 30 Apr. 2014, https://slate.com/technology/2014/04/antibiotics-in-chicken-vencomatic-patio-system-makes-birds-healthier-drug-free.html.

- Bunge, Jacob. “Perdue Farms Eliminated Antibiotics from Chicken Supply.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 6 Oct. 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/perdue-farms-eliminated-all-antibiotics-from-its-chicken-supply-1475775456.

- McKenna, Maryn. “Antibiotic Use in U.S. Farm Animals Was Falling. Now It’s Not.” Wired, Conde Nast, 14 Dec. 2021, https://www.wired.com/story/antibiotic-use-in-us-farm-animals-was-falling-now-its-not/.

- Entis, Laura. “Will the Worst Bird Flu Outbreak in U.S. History Finally Make Us Reconsider Factory Farming Chicken?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 14 July 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/vital-signs/2015/jul/14/bird-flu-devastation-highlights-unsustainability-of-commercial-chicken-farming.

- “Bird Flu Virus Infections in Humans.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 4 May 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/avian-in-humans.htm.

- Ranganathan, Janet, et al. “Shifting Diets for a Sustainable Food Future: Creating a Sustainable Food Future, Installment Eleven.” WRI, World Resources Institute, Apr. 2016, https://files.wri.org/s3fs-public/Shifting_Diets_for_a_Sustainable_Food_Future_1.pdf.

- Mekonnen, M. M., and A. Y. Hoekstra. “Volume 1: Main Report – Waterfootprint.org.” Water Footprint Network, UNESCO-IHE, Dec. 2010, https://www.waterfootprint.org/resources/Report-48-WaterFootprint-AnimalProducts-Vol1.pdf.

- Shanker, Deena. “If You’Re Not Cooking With Air-Chilled Chicken, You’Re Doing It Wrong.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 3 Aug. 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-08-03/why-you-should-cook-air-chilled-chicken.

- Goss, Scott. “DNREC Finds High Levels of Fecal Coliform at Sussex Plant.” Delaware Online, The News Journal, 10 Nov. 2017, https://www.delawareonline.com/story/money/business/2017/11/10/mountaire-farms-polluting-sussex-county-groundwater-state-says/848548001/.

- Rentsch, Julia. “Chesapeake Bay Nitrogen Pollution from Poultry Likely Higher than EPA Estimates: Report.” The Daily Times, Salisbury Daily Times, 29 Apr. 2020, https://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/2020/04/29/chickens-add-more-chesapeake-bay-nitrogen-pollution-than-epa-thought-environmental-group-report/3002894001/.

- “Harmful Algal Blooms in the Chesapeake Bay Are Becoming More Frequent.” ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, 11 May 2015, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/05/150511125219.htm.

- “Ammonia Emissions from Poultry Industry More Harmful to Chesapeake Bay than Previously Thought.” Environmental Integrity Project, 22 Jan. 2018, https://www.environmentalintegrity.org/news/ammonia-emissions/.

- “Big Chicken: Pollution and Industrial Poultry Production in America.” Pew, Pew Charitable Trusts, 27 Jan. 2011, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/peg/publications/report/pegbigchickenjuly2011pdf.pdf?la=en&hash=6F6A5C0C1C3CE4030044B9857FE8BF86FD0E4ED1.

- Ibid.

- “Methemoglobinemia (MetHb): Symptoms, Causes & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 2023, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24115-methemoglobinemia.

- Brown, Keri. “When a Chicken Farm Moves next Door, Odor May Not Be the Only Problem.” NPR, NPR, 24 Jan. 2016, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/01/24/463976110/when-a-chicken-farm-moves-next-door-odor-may-not-be-the-only-problem.

- Philpott, Tom. “How Factory Farms Play Chicken with Antibiotics.” Mother Jones, 16 May 2016, https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2016/05/perdue-antibiotic-free-chicken-meat-resistance/.

- “Status Information: A139, R144, H3929.” South Carolina Legislature, South Carolina Legislative Services Agency , 2018, https://www.scstatehouse.gov/sess122_2017-2018/bills/3929.htm.

- Lefler, Dion, and Johnathan Shorman. “Sedgwick County Withdraws Bid for Tyson Chicken Plant.” The Wichita Eagle, The McClatchy Media Network, 7 Dec. 2017, https://www.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article188550779.html.

- Frese, David. “Tyson Foods, Kansas Officials Answer Town’s Fears about Secrecy, Immigrants & Chickens.” The Kansas City Star, The McClatchy Media Network, 14 Sept. 2017, https://www.kansascity.com/news/politics-government/article173193136.html.

- Kite, Allison. “Senate Approves Concentration of Chicken Houses.” Cjonline, Topeka Capital-Journal, 23 Feb. 2018, https://www.cjonline.com/news/20180222/kansas-senate-approves-concentration-of-chicken-houses-after-public-outcry-over-tyson.

- McGee, Jamie. “Tyson Chicken Plant: Rejected in Kansas, Welcomed in Tennessee.” The Tennessean, USA Today Network, 23 Mar. 2018, https://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2018/03/23/tyson-chicken-plant-tennessee-kansas-humbolt/367236002/.

- Reicher, Mike. “Tennessee Lawmakers Take up Bill to Roll Back Water Quality Regulations at Livestock Farms.” The Tennessean, USA Today Network, 20 Feb. 2018, https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/2018/02/20/tennessee-lawmakers-take-up-bill-roll-back-water-quality-regulations-livestock-farms/355297002/.

- Fassler, Joe. “Does Free-Range Chicken Taste Better?” The Counter, 30 Mar. n.d., https://thecounter.org/do-free-range-chickens-taste-better/.

- Strom, Stephanie. “A Chicken That Grows Slower and Tastes Better.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 May 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/01/dining/chicken-perdue-slow-growth-breed.html.

- Munniksma, Lisa. “How to Find and Cook a Heritage Chicken.” Modern Farmer, Modern Farmer Media, 6 Mar. 2014, https://modernfarmer.com/2014/03/find-cook-heritage-chicken/.

- “ Large-Scale Pastured Poultry Farming in the U.S. (Research Brief #63).” Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1 Jan. 2003, https://cias.wisc.edu/livestock/large-scale-pastured-poultry-farming-in-the-us/.